NOTE: This is a reproduction of my 30-minute (whirlwind) presentation at the Librarians' Knowledge Sharing Workshop held in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, in November 2017. I have tried to note which slides relate to which points, within the text below.

Diversity is a hot topic in children’s and YA literature at the moment, but for us working as school librarians in international schools, it’s always been an issue as we strive to provide access to texts that reflect our varied student populations, curriculum concerns, local context, and worldview.

NETWORK-BASED ANNUAL BOOK AWARDS

One of the most fertile channels for discovering new literature to bring into our schools is the annual book award shortlists generated by country-based international school librarian networks. Most of you in the audience have participated in one or more of these, whether getting your students to read and vote on the books or working with your network colleagues to help choose books to shortlist every year.

Of all the experiences of being in a locally-based international school teacher librarian network like ISLN in Singapore or BLISS in Bangkok, the most rewarding aspect for me has been being involved in the running of their annual book awards. Serving on such a committee means belonging to a group dedicated to finding books that would be great book group choices for students of different ages. I love the ongoing purposeful interaction with other teacher-librarians, as we struggle to satisfy our criteria and deadlines.

Asia seems to be where this international school library phenomenon started. (Slide 2)

When Barb Reid and I began the Red Dot book awards in Singapore, now in its 9th year, we were inspired by China with its Panda Awards and Japan with its Sakura Medal. Later, Hong Kong, Korea, and Thailand set up awards, as did Switzerland and Germany. More recently I discovered the Jarul Award in India, which is for picture books published in India.

- Singapore: Red Dot Awards

- China: Panda Awards

- Japan: Sakura Medal

- Hong Kong: Golden Dragon Book Awards

- Thailand: Bangkok Book Awards

- South Korea: Morning Calm Medal

- Switzerland: Golden Cow Bell Awards

- Germany: Hansel and Gretel Award

- India: Jarul Book Award

All the awards listed above have varying criteria and structure: in their number of list categories (e.g., Singapore produces 4 lists, Bangkok 3), number of titles on a list (e.g., Singapore has 8 titles per list, Bangkok 6), criteria for inclusion (e.g., published how recently - Singapore is the past 4 years, Bangkok the past 5), timing of the shortlist announcement/voting cycle, and activities related to the annual results (e.g., Singapore has had a Readers Cup competition, Switzerland produces literal Swiss cow bells (custom-cast) to send to each author-winner).

The less concrete but more important selection criteria - e.g., "excellence" but also "diversity of author, theme, genre, setting and narrative style" (Bangkok Book Awards) - are an ongoing challenge (as I will discuss in detail further on).

Each network also has its own time, space, and financial constraints regarding the process of determining a longlist and shortlist.

Is it easy to meet in person to discuss books, or is the book group in effective a virtual one? Does that determine how many people can be on the committee? Who should provide input to the longlist -- and shortlist? (What about students?) How many people will have time to read or ability to access each longlist book in order to contribute to the shortlist decision? Given the budget/acquisition cycle in the school or country, when is the ideal time to publish the shortlists so books will be in the hands of students soon enough and long enough to be able to vote? (And how important is the voting element anyway?)

BOOK AWARD MODELS

Let's step back and consider four major models of book awards. (Slide 5)

Popular Survey -- one person, one vote -- epitomized by the BBC Big Read (first famously done in 2003) and the annual Goodreads Choice Awards. These awards are summative and democratic in nature. One such annual popular survey for children's literature is the K.O.A.L.A. (Kids Own Australian Literature Award), which has been going for 31 years now (more re this award below).

- Professionally Curated "Best of" Booklists -- the most obvious examples for children's literature are the annual national ones, often organized by library associations, such as the US Newbery/Caldecott, the UK Carnegie/Greenaway, the Australian CBCA "Book of the Year", the Canadian CCBC Book Awards, and the NZ Book Awards -- though there is also the international biennial IBBY Hans Christian Andersen ones for authors/illustrators. These are summative within a year, but formative over time of a canon.

- Book Tournaments via Brackets -- where pairs of books are pitted against each other in a series of rounds until a final winner is declared (by a judge or team of judges). In children's literature the most prominent example is School Library Journal's annual "Battle of the Kids' Books" -- though there are adult ones as well, e.g., The Morning News Tournament of Books. Note there is a free online app called BracketCloud that allows anyone to set up their own single or double elimination brackets, e.g., see this description of having students set their own personal reading challenges using Google Drive -- so they are the "judge."

- One Book, One Community - Not really an award, but a popular reading initiative where a particular book is chosen (by professionals) for a group (whether grade, school, city, or state) to read and discuss within a given time span. See this Wikipedia entry for many examples of such a shared book experience. A powerful way to extend this would be to choose a title that has different editions, i.e., picture book version, young readers edition, and adult edition (including print, digital, and audio formats), so a wider range of readers can participate.

Most of our network awards fall into the "professionally curated" bucket. And most of us then have the students vote for their own personal favorite such that winners can be announced. However, a point of criticism has been that students are only able to vote for something on a list that an adult has pre-selected -- which can be called a delusion of democracy.

But what's the important thing here? The lists? The books? The reading? Student agency in determining lists? The structured competition?

Perhaps we need to ask ourselves: Why? Why did our networks set up these awards? Why does each school participate each year? The answers vary.

For example, the instigation for the Red Dot Book Awards in Singapore grew out of Barb Reid and I being concerned about the multiple copies of the "same old books" sitting on the shelves in the primary school reading cupboards, reflecting "classics" from the dominant culture of teachers working in our respective international schools.

We wanted a reading initiative that would allow us to regularly refresh the book cupboards with recent literature reflecting the diversity of our community and supporting our school values of internationalism -- i.e., books worth buying multiple copies of and discussing. The professionally curated "award" list was a good vehicle because what we really wanted was to invest in some books for a "one book, one community" reading experience. Voting for the "best book" from the shortlist is just a diversionary tactic -- to encourage the reading.

I'm now thinking I want to complement that kind of award with an annual popular survey one -- to address the goal of kids sharing their favorite reading with the community, no matter where the books come from. For that kind of a "children's choice" popularity contest I am inspired by the K.O.A.L.A. awards in Australia, which I learned about while visiting Cranbrook Junior School in Sydney a few months ago. (Slide 6)

Megan Light, the primary teacher-librarian there and one of the award's administrators, explained how the annual awards are structured to be both formative and summative. The shortlists are the top 10 books that kids nominate (criteria: Australian and published within the past ten years) in four age categories. If titles are shortlisted five times without winning, then they go into the K.O.A.L.A. Hall of Fame (a wonderful summative list along with the cumulative winners list). Megan pointed out that the nomination process is a good excuse to discuss the award's criteria with students, e.g., what makes a book Australian, how to check the "publication age" of a book, and what age of reader is a book best suited for.

THE CURATION TASK

In choosing books for the curated-list kind of award, we adults also sometimes struggle to figure out the right age category for a particular title, but the bigger challenge is in determining what set of titles in a category will satisfy the not-so-concrete criteria of having a "broad range of books" across the shortlist, which we all agree (to varying degrees) is important. (Slide 7)

Stealing ideas from other networks' annual shortlists is the easiest path. Hence, there is a great amount of overlap between our choices, all the while coveting works from Asia as well as works in translation. And we are all looking for books that relate to international issues.

Refugees are an obvious topical star at the moment. Last year Singapore chose the Canadian title, "Stormy Seas" -- a large-format upper-primary/middle school picture book for older readers with parallel storylines of refugees from Nazi Germany, Vietnam, Cuba, Afghanistan, and the Ivory Coast -- which we in Bangkok have also selected. Interestingly, Alan Gratz (USA) came out with a similar (chapter) book called "Refugee," featuring three narratives based on Nazi Germany, Cuba, and Syria. Sometimes we're just spoiled for choice! (Slide 8)

I recently read a 2016 Routledge academic text devoted to analyzing children's books awards, with chapters written by different experts -- Prizing Children's Literature: The Cultural Politics of Children's Book Awards. See Slide 9 for the cover, and slide 10 for a screenshot of the table of contents as well as the purchase price. I suggest you peruse the free preview via Google Books before deciding whether to buy, though I highly recommend the contents on the whole.

The chapter by Claire Bradford on Australian books (now eligible for the the US (ALA) Printz award) is particularly interesting, where the conclusion is that only Australian books that are not "too" Australian succeed in the American arena. June Cummins's chapter on how the American Newbery is not really about excellence, but is instead an identity-based award, deserves attention -- as does her argument for the use of intersectionality theory. (Slide 11)

A BALANCED MEAL

When it comes to generating a diverse shortlist, my best metaphor is the balanced meal (Slide 12) -- and this begs the question of what attributes or facets we should all be considering in terms of diversity.

Luckily the people at Kirkus Review (in collaboration with Baker & Taylor, the booksellers) published some diversity collection lists last September, and I did a basic reverse-engineering of their taxonomy. (See Slides 13-17 inclusive.)

Pay attention! Because all of us need to be considering our own library catalogs (and subject headings) in light of the work they've done, though their facets are aimed at the American context.

Kirkus tagged books by four diverse elements: race/culture, religion, gender expression, and/or disability. (Slide 14)

And for each of those, they then categorized the book to what extent that feature is present. CENTRAL = central to the book; IDENTIFICATION = relevant to the plot; or INCLUSION = when the diverse element is part of the background or seems to be normal. (Slide 13)

Besides those attributes, they also looked at types of experience for the characters in the book in relation to the diversity (e.g., coming out, reckoning with, etc.) and whether they were lead characters, background characters, ensemble casts, or families. Of course, they also considered what I would call "standard variables" -- e,g, genre, time (past, future, or present), and the age of the assumed reader. (Slide 15)

As international school educators, we also consider how books can be linked to our schools' values, mission statements, and curriculum. For example, those of us working in IB (International Baccalaureate) schools are always on the lookout for books that reflect the Learner Profile as well as ones to support whatever PSE (personal, social, and emotional) curriculum is used (e.g., see this UWCSEA East Primary Libguide). (Slide 17)

If you're interested in a taxonomy for Social and Emotional Learning (SEL), look at the results of Myra Garces-Bacsal's ongoing project for the Office of Educational Research at the National Institute of Education (NIE) in Singapore (based on the CASEL project in the US), which she is publishing as a Social and Emotional Bookshelf on her blog. The more raw tags for each book can be seen on her LibraryThing catalog for Gathering Books.

EXPANDING OUR BORDERS

As international schools, probably one of the most important elements of diversity we want to consider is geographic connections, whether local, national, or regional. Like Kirkus's distinction between three degrees of representation of diversity in a book, we might consider three types of connection -- 1) geography as it relates to the characters or setting of the text; 2) the background or origin of the author; and 3) location of the publisher.

This raises the question of, who wrote it? And who did they write it for? Looking a book in terms of accuracy (e.g., did they get the details right?), authority (e.g., what culture is the author/publisher from?), and authenticity (e.g., is it realistic? from what perspective? is it convincing?). (Slide 18)

In considering a book with a particular geographic orientation, we also have to ask questions in relation to the potential reader (i.e., students in our schools). 1) Will it appeal to them? 2) Is it easily available, in the sense, will we be able to source it and get it into our libraries? 3) Is it accessible to the reader (e.g., does it require background knowledge or a glossary or translation of terms in order to be understandable? how close it it to the students' current experiences?). (Slide 19)

For example, I recently read "A Moment Comes" by Jennifer Bradbury as part of the shortlist process for the BLISS Book Awards. It's historical fiction set during the partition of India in 1947 and features three narrative perspectives (a Muslim boy, a Sikh girl, and a British girl). Indian terms are used throughout -- and like a good reader, I persevered and tried to get the meaning from the context. Only at the end did I discover a glossary, explaining all the terms, which would have been useful to me as I read along (sigh). As the name "Jennifer Bradley" isn't particularly Indian, I did a bit of online sleuthing to determine whether she was writing from a position of accuracy and authenticity -- and it turns out she spent a year living in the Punjab. (Slide 20)

Another book I read for the shortlist was "A Flame in the Mist" - fantasy historical fiction set in samurai Japan -- which also provides a glossary in the back that I also didn't realize was there until I finished the book (sigh sigh). My research on the author, Renee Ahdieh, revealed she is an American whose mother is from South Korea, so she has Asian roots. (Slide 21)

For authenticity and accuracy about a geographical region, translations are the best bet -- and for the Red Dot Book Awards we have always tried to include them, watching the winners of awards like the Batchelder Award in the US and the Marsh Award in the UK. Similarly the Hans Christian Andersen Award, probably the most important international children's book award, is an excellent source of books that provide geographical (and linguistic) diversity.

One past choice -- "Moribito" by Nahoko Uehashi (winner of the 2014 Hans Christian Andersen) -- is a translation of a popular Japanese series that features a female samurai -- so a natural read-on recommendation for "A Flame in the Mist" mentioned above. (Slide 22).

"Bronze and Sunflower" by Cao Wenxuan (the 2016 winner and first Chinese author) has been a shortlist choice for several of the international school library book awards. Set during the Cultural Revolution, the slow-moving but heartwarming novel is part of a very popular series in China. It's exactly the kind of book our students might not have discovered without our intervention. One of our key functions is to expose readers to books they otherwise might have missed or books with slightly different writing styles due to cultural differences. (Slide 23)

There is a wonderful blog and Facebook Group called the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative (GLII) which promotes books in translation.

The founder, Rachel Hildebrandt, has recently organized people to develop online catalogs of children's and young adult literature in translation using LibraryThing. The number of languages will only expand over time. (Slide 24)

How are cultural differences bridged in texts? How do authors and translators ease readers into unfamiliar territory and accommodate varying expectations (beyond the use of glossaries noted above)?

One of my favorite bloggers, Venkatesh Rao on Ribbonfarm, who usually writes about technology and business, published a blog post in 2009 called “The Rhetoric of the Hyperlink,” in which he discusses the choices available to writers in light of the issue of potentially different cultural markets. NB: He was born in India but now lives and works in the US.

1). The Fishbowl Style - where you assume everyone is swimming in the same water of understanding - I.e. you don’t explain anything because you are writing from within a culture;

2) The Expository Style - where you (laboriously) explain everything as you go for “outsider” readers;

3). The Global Contextual Style - where local/global cultural analogies are made, e.g., reference a Bollywood actor, but compare them to a supposedly well-known Hollywood one;

4). The Literary Way - what he calls the “Salman Rushdie method” — where you just write creatively and demand the reader work to construct meaning - or live with the opacity!

Rao argues that hyperlinks offer such a great potential to writers today, to allow "Fishbowl" writing thanks to hyperlinks behind words that might require cultural explanation. While this is common in online blog and journalistic writing, it has yet to be fully utilized in many (any?) of the ebooks available, especially not mainstream literature. Instead the internet is assumed to be sitting there as one big online “glossary.” (Slides 25-26)

DEEPER INTO THE WORLD

When it comes to world fiction, there’s one book I highly recommend as a tool to improve the balance of your collection and the information in your catalog (i.e., intellectual access or subject headings): "The Complete World Guide to Contemporary Fiction" by Michael Orthofer. (Slide 27-28)

Unlike the previous book suggestion, this one is highly affordable - about US$15 for the ebook or paperback — plus he has an information-packed website of reviews. In the book, Orthofer provides a narrative tour of authors from different countries or regions. This helps me look for titles in my collection that I need to add subject headings to, e.g., "Translations -- from BLAH language -- into BLAH language" -- as well as geographic connections. (If you are fascinated by who would produce such a labor of love, read this 2016 New Yorker profile of Orthofer.)

Another resource you might consider if you’re really interested in what makes certain books culturally specific and to what extent those books are accessible to readers from other cultures, see this Routledge academic text "Subjectivity in Asian Children’s Literature and Film: Global Theories and Implications (Children's Literature and Culture)" edited by John Stephens, a professor of children's literature at Macquarie University in Australia.

See slides 29-30 for screenshots of the chapters and authors, which cover a range of Asian countries and formats. Unfortunately this book is fairly expensive (even rented as a textbook), but luckily many parts of it can be read via Google Books here.

TRACKING DIVERSITY

As we international teacher-librarians on the award committees come together each year to find a balanced list of titles, I’m always curious about how everyone tracks their reading over the year, looking for our variables of diversity.

Solving this problem of diversity -- what I called the "balanced basket" problem (in writing about the Red Dot Book awards back in 2014) -- can take up 80% of the time (according to the Pareto principle of 80/20 split). In Singapore this often meant lugging bags of books to evenings meet-ups, sharing and swapping titles, in the hopes of getting someone else to confirm that a work would work perfectly to enhance our offerings.

In slide 31 are photos of some paper bookmarks we used at UWCSEA East to quickly record things about a book as we read it — what country it’s from, what values it connects with, genres, grade-level appropriateness, literary features, etc. I use Goodreads in the same way - setting up bookshelves for each attribute. Goodreads isn't the most perfect social reading site, but it is the most accessible.

This raises the question of how we provide intellectual access to the diversity of our collections through our library catalog. One way to make these variables searchable is via subject headings.

For example, if we have two Follett Destiny catalogs at our school (primary and secondary) and both want to track books about gender issues, we might agree that both catalogs will use a local subject heading of "LGBT Plus - Gender roles - Free To Be@NIST" (where Free to Be@NIST is the name of the student group looking at gender issues). This gets around the problem of teaching people what acronym to search for (LGBTQIAP+ or LGBTQ+ or GLBT, etc.).

When it comes to genre identification, our primary and secondary catalogs might use different terms when talking to students, so then we could each use a site-specific subject heading (rather than a shared local one), so only patrons of the secondary library would be able to search for and see "Genre - Realistic / contemporary fiction - NIST" -- whereas the primary library catalog might use just "Realistic fiction". (Slide 32)

Slide 33 shows how we use subject headings to track which books in our catalog reflect values in the IB Learner Profile or ones associated with Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) -- as well as geographic connections. (Slide 33)

WHAT'S IN A BALANCED BASKET?

So back to the problem of how our network committees get balanced baskets of shortlisted titles.

How many aspects of diversity are we are looking for?

Ensuring a range of genres is the usual starting place. When I came to NIST, the Y8 team asked me to run sessions with the kids looking at these genres: nonfiction, horror/supernatural, humor, fantasy historical fiction, realistic, science fiction/dystopia, and graphic books. (Slide 35)

But in talking to students about genres, I realized you can break them down more simply into three baskets based on a continuum, moving from unreal to real: Unrealistic Fiction, Realistic Fiction, and Nonfiction. (Slide 36)

By applying the dimension of time (past, present, and future) to those three baskets, you can start to map more specific genres. For example, if realistic fiction about the past is "historical fiction," then unrealistic fiction about the past might be "alternative history" or "historical fantasy" -- and nonfiction about the past is history or biography. (Slide 37)

Adding in an emotional response to a book gets you to more genres, e.g., realistic fiction in the present time could be either Mystery, Horror, Thriller, Humor, or Romance -- depending on the emotion it invokes. Slide 38 shows some emoji-book-review bookmarks we use, asking students to consider whether a book made them cry, smile, think, or be scared.

But the basics are the three categories: Unrealistic Fiction, Realistic Fiction, and Nonfiction.

What if each professional longlist reader for our book awards came to the table prepared with a basket of books, balanced for the following variables (while also adhering to the publication time conditions, e.g., with the past 4 years)? (Slide 39)

- Genres (unrealistic fiction, realistic fiction, and nonfiction)

- Local / Regional / Global connection (whether author, setting, or publisher)

- Diversity / Social / Global issues

- Male/Female appeal

- Translation

- Format, welcoming any:

- Graphic / Wordless

- Verse novel

- Poetry

- Short stories

What tool might allow us to share our respective proposed baskets? Barb and I dummied up a Padlet example -- see Slide 40. It's just a suggestion. We'll see how it goes in this next cycle of longlist to shortlist.

The geographical balance is often the hardest to ensure. Working on the Red Dot Books shortlists, we might find ourselves with a great set of titles, but then suddenly realize when we looked more closely that we had no Australian books or no Canadian books -- and would have to go back through our longlist more carefully. How much easier if everyone had noted geographic connections as they read throughout the year.

But we always got there in the end, as the backlist of shortlists over the past 9 years of the Singapore Red Dot books demonstrate (see them all here). Getting the balance right takes time, but is so worth the effort.

LEADership and diversity

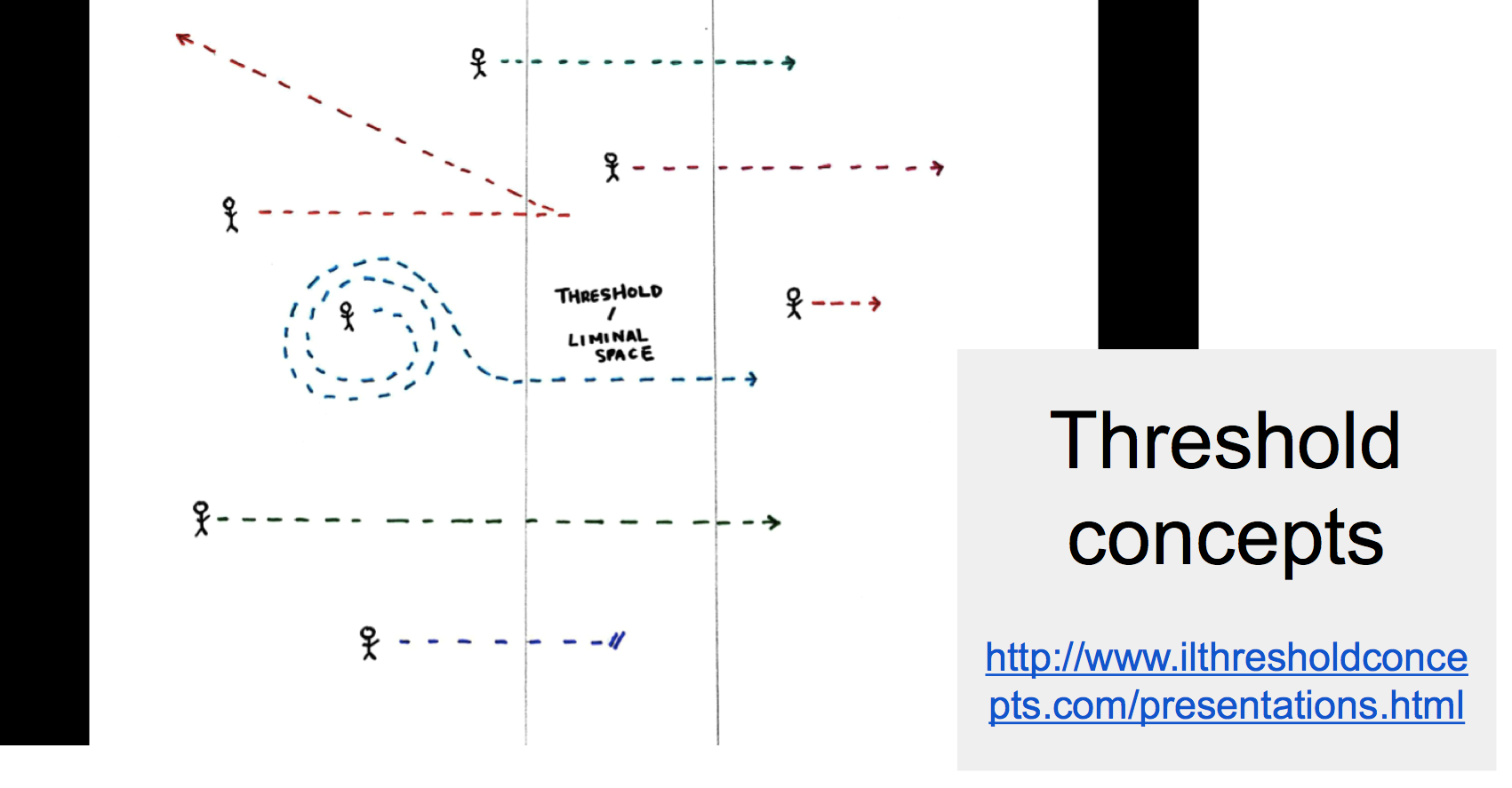

I've been reading and listening to Peter Senge, the leadership and management change guru, quite a bit recently. He talks about the the root of the word "leader" being one who steps over the threshold, lifting their foot in vulnerability, and doing what's right for the whole, moving forward. He says real cultural change is inquiry into our blind spots and letting go. (Slide 41)

We as teacher-librarians must be good leaders of diversity. We can help our community ask, What is self? What is other? Reading and noting what aspects of diversity resonate with each of us as we read can help. We can't promote diversity without knowing ourselves and our own community.

We have the power to put texts in the reach of our students that will speak across cultural thresholds.