I've been meaning to blog about Andrew Abbott, a sociology professor at the University of Chicago, for two years now -- ever since I saw him present at the American Library Association conference in Chicago.

Though his sphere is graduate students for the most part, his insights -- as a sociologist -- into how students do (or don't do) research and use libraries can be applied to all of us as professional learners -- and to our own (younger) students. Abbott clearly loves libraries and has written quite a few papers on the history of academic libraries and research tools. Besides what nuggets of notes I'm going to pass on here, you should go to his webpage at the University of Chicago and read a few of his papers related to libraries - in particular, The Future of Knowing.

First of all, he sees teaching research as basically teaching project management -- and argues that, because teaching is a necessary means of knowing what you do, self-ethnography is the only way to really teach researching. He forces graduate students to keep diaries and then to teach others what they've learned about themselves as researchers. (Good 'ole reflection and communication...)

Abbott claims experts mainly wander in the library. They don't particularly take advantage of general bibliographies or reference books (or even the library reference desk). Instead they prefer to mine (or ransack) other people's bibliographies - extensively. Which is good advice for any researcher -- even a someone starting at Wikipedia -- i.e., to go to the bottom of the page and find out where they got their information.

As library research is fundamentally not linear, students are always in danger of getting lost. Being a mature researcher is about learning what to ignore. This is where (that trendy word) "mindfulness" comes in. Trying to stay alert, to see beyond the frame of what is in front of you, to keep your peripheral vision ready to sense the bigger picture. (Who is that person behind the curtain? And why are they saying what they're saying?)

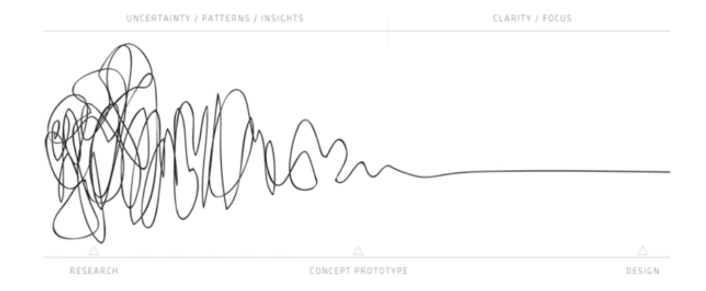

Design thinking squiggle (originally from IDEO; see video explanation) - which I think is a perfect image for how library research goes....

Abbott argues that research is not about finding things. It's about knowing and guessing what to look for -- and then recognizing when you've found something you ought to have looked for in the first place. That wandering time may feel aimless or useless -- until you find the thing that matters. The thing that answers your question -- or changes your question.

"Follow your passion" is a popular refrain -- when asking students to come up with their research question (e.g., in the IB Diploma Extended Essay process). I counsel students looking for a research question to "Follow your attention." (Again, mindfulness....)

What do you click on? What books do you pick up from a library display? Notice what your brain desires. Maybe your subconscious (that fast thinking part of your brain) is trying to tell you something. Because that may lead you to the best research question -- for you.

Abbott points out that sometimes the best thing to research is the thing you have the most data about. Work with the materials at hand. Find a question that interests you within a detailed realm you have access to. Which brings up that design thinking model on the intersection of desirability (interest), feasibility (assigned task), and viability (resources at hand). Viability -- what you have to work with -- is key.

See previous blog post on Design Thinking and Research....

Students must realize is that all research questions are puzzles within a puzzle -- and every answer is only true within a particular context. As he says:

A given piece of information or interpretation is knowledge only with respect to a particular project of knowing. Until you have your project figured out, you can't say what knowledge is.

Which reminds me of another session I attended at that ALA, where a university librarian told how he would let students browse a visual photographic archive they had and ask them to choose an image (e.g., a page from a 1950s women's magazine or a political cartoon from a newspaper in the 1880s) and then to formulate a research question for which that image would be a primary source. And then to consider, for what question would it be a secondary source? (Which feeds back into one of the ACRL information literacy threshold concepts - Authority is constructed and contextual.)

Abbott has his own list of threshold concepts he tries to get across to students.

One is the important difference between the (keyword-based) concordance-style indexing found via an internet search and the (ideas-based) subject indexing in the back of old-fashioned books (done by people, though computers are currently trying to learn it).

Finding things on the internet is the students' principal model of cognition. Their sad belief is that the key to a book is in some subset of sentences that you can search, highlight, and copy.

I love how Abbott enforced close reading in his classroom. In "The Future of Knowing" he talks about how he assigned undergraduates as homework to memorize 2 or 3 sentences from the required reading (e.g., Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations) -- and silently meditate on them for 15 minutes. In class he then asked students to write those sentences down from memory -- to hand to him each day. He says this exercise transformed their reading -- which for him means "using a text as a stimulus for a complex reflection." The paper the students were later assigned to write on Adam Smith was to take five of their meditation passages and turn them into an argument about Adam Smith.

He believes students need to appreciate that books, by virtue of their length, have arguments and direction that websites often don't. He says the best students are the ones who can create an outline of a book's argument, revealing the structure of the text.

Anyway, go read him yourself. His curmudgeonly complaints about undergraduate and graduate students as researchers will be terribly familiar, but I appreciate his long view as an academic and a sociologist, and he reminds me about the importance -- and difficulty -- of meta-cognition in the research process.