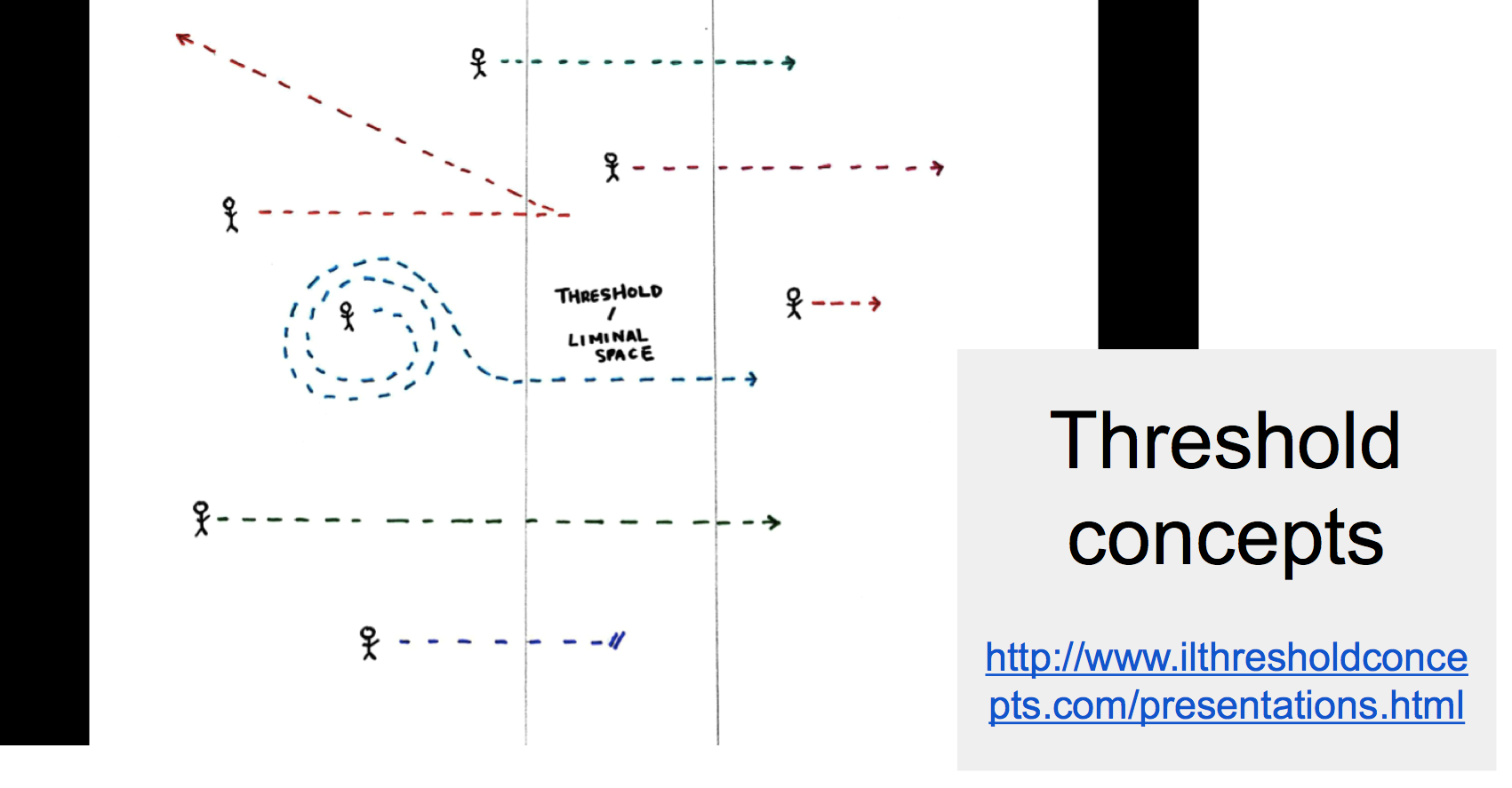

Threshold concepts are something every librarian concerned with research needs to be familiar with. That's why I was thrilled that Debbie Abilock (of Noodletools) and Sue Smith (of the Harker School) did a session on it at the Research Relevance Colloquium in June. (See my previous blog posts on Research Relevance: here and here.)

I wrote up my introduction to threshold concepts a year ago - after ALA 2014 - see this blog post (just scroll down to find the section - it's too much to reproduce here, but the links are worth it).

Since then ACRL (the American Association of College Research Librarians) has officially published their Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education which incorporates these six threshold concepts.

- Authority is Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation is a Process

- Information Has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

It's hard to argue with any of them -- obvious as they may seem. We forget how alien some of these assumed understandings are to students. That's why I live by metaphors. And threshold concepts have helped to focus my use of them.

I asked the audience at Research Relevance to suggest new metaphors -- and here are some responses:

- a search engine like Google is like "trail mix" - returning results include some M&Ms, some raisins, some peanuts - while a database is like a whole bag of M&Ms -- all good results

- a group project is like a music quartet - each contributing to the whole beautiful sound

- a database is like a bathtub filled with water for a particular size and purpose, while Google is like a river, whose flow is unpredictable and aimless

I particularly like (the dead white male professor) Kenneth Burke's description of the metaphor of the "unending conversation" of academic discourse ->

"Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally's assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress." [source]

Debbie and Sue spoke about giving students three information sources in three different arenas: e.g., a tweet, a newspaper, and a journal -- by the same author (e.g., Michael Kraus). To show how authority is perceived from different angles.

Just as I would tell my grade 11 IB Diploma students setting out on their Extended Essays: "go to the library's physical bookshelves, find a book, look at the author (the expert), Google them to see their most up-to-date outpourings, do they have a blog, do they tweet? -- find your experts first -- then find out where they have said what you need to cite -- and choose the most academic channel of their output."

I caution students that their biggest danger is not finding the (right? best? cutting-edge?) experts in your field. (The Ignorance Trap: You don't know what you don't know....) Looking for published book authors first is a safe bet. Someone who has gotten someone else to pay to print their thoughts is someone maybe worth listening to. On the other hand, they may be already out-of-date. Everything depends on the context.

We teacher-librarians talked about disciplinary literacy -- and asking teachers in departments, "How do you construct knowledge in your discipline?" -- and making them define it, e.g., in a Google Doc.

We talked about how students don't like sources that don't support their thesis - they don't know what to do with them.

We talked about how competence in research is a developmental sequence, like beads on a string. You may not see all students through all the stages, where Stage 1 is concrete truth (novice), Stage 2 is opinion, and Stage 3 is a reasoned opinion. And we recognized that these stages are not age-dependent. (Think: Philosophy for Children - http://p4c.com/).

Annotated bibliographies are often a good litmus test of where students are. Where annotations are minimally: Describe + Understand + Compare.

Having students think of a bibliography like a detailed ingredient list to a foodstuff or meal is still my favorite metaphor. You may not need to mention everyday ingredients like water or salt (commonly known stuff), but you absolutely must cite anything flavorful or key to the recipe.

Threshold concepts are key. Metaphors are key. And school librarians need to find the right metaphors for their students. Context is key.